A medical objective function

The ultimate goal—or “objective function”—of any health-care professional is to maximize patients’ expected quality-weighted longevity. At this introductory stage, we are not assuming any particular measure of quality-weighted longevity (e.g. quality-adjusted life years, disability-adjusted life years, years lived with disability, etc.). Rather, we are simply assuming that the relevant outcome metric is some combination of quality of life and longevity. Since (A) one must often sacrifice quality of life for longevity or vice-versa, and (B) quality of life is naturally conceptualized as a measure spanning the 0 to 1 (or 0\% to 100\%) range, it is natural to construct the clinical objective function with the central feature of quality-weighted duration of life. We will denote quality-weighted longevity by $\mathcal{Q}$, and note that it is a function that depends on a set of variables corresponding to patient characteristics (we’ll denote the set of these variables as $\mathcal{D}$ for “data”), and a set of parameters $\boldsymbol\Theta$ which reflect the effects that each variable has on quality-weighted longevity. The function $\mathcal{Q}$ can thus be represented as follows:

which can be decomposed into the quality-weight component, $\omega(t)$, and survival probability component $S(t)$, both of which are functions of time, $0 < t < T$, where $T$ denotes the individual’s time of death. In survival analysis, the survival function $S(t)$ is commonly defined as

where $P(T>t)$ is the probability that an individual’s time of death $T$ will occur after time $t$. This can be intuitively understood by considering that at an initial measurement time $t=0$, the individual’s probability dying after that time is 100\%, but this probability decreases the further one looks ahead beyond $t = 0$.

Since both quality of life at some future time $\omega(t)$ and survival probability at some future time $S(t)$ are both uncertain, if the clinician seeks to maximize quality-weighted longevity, he or she must estimate the net-present quality-weighted longevity, which we will denote by $\mathcal{Q}_0$, where the subscript 0 denotes that the estimate is made at time $t=0$:

Although it is easy to formulate this equation for the general case at time $t$, we are only concerned with the $t=0$ case (i.e. at the present clinical interaction). This equation states that the individual’s expected total quality-weighted longevity as of time $t=0$ (the present) is equal to the product of quality and survival probability from the present onward. The subscripts on $\boldsymbol\theta_\omega$ and $\boldsymbol\theta_S$ denote the components of $\boldsymbol\Theta = \lbrace \boldsymbol\theta_\omega, \boldsymbol\theta_S \rbrace$ that parameterize the quality-weight function $\omega$ and the survival function $S$, respectively.

The estimate of $\mathcal{Q} _0$ is a random variable and so we must incorporate some measure of uncertainty. If one assumes that $\mathcal{Q} _0$ is normally distributed with mean $\mu _\mathcal{Q}$ and variance $\hat{\sigma} _\mathcal{Q}^2$,

then the expected value of $\mathcal{Q}_0$, which we will denote by the conventional hat $\hat{\mathcal{Q}}_0$ would be computed as

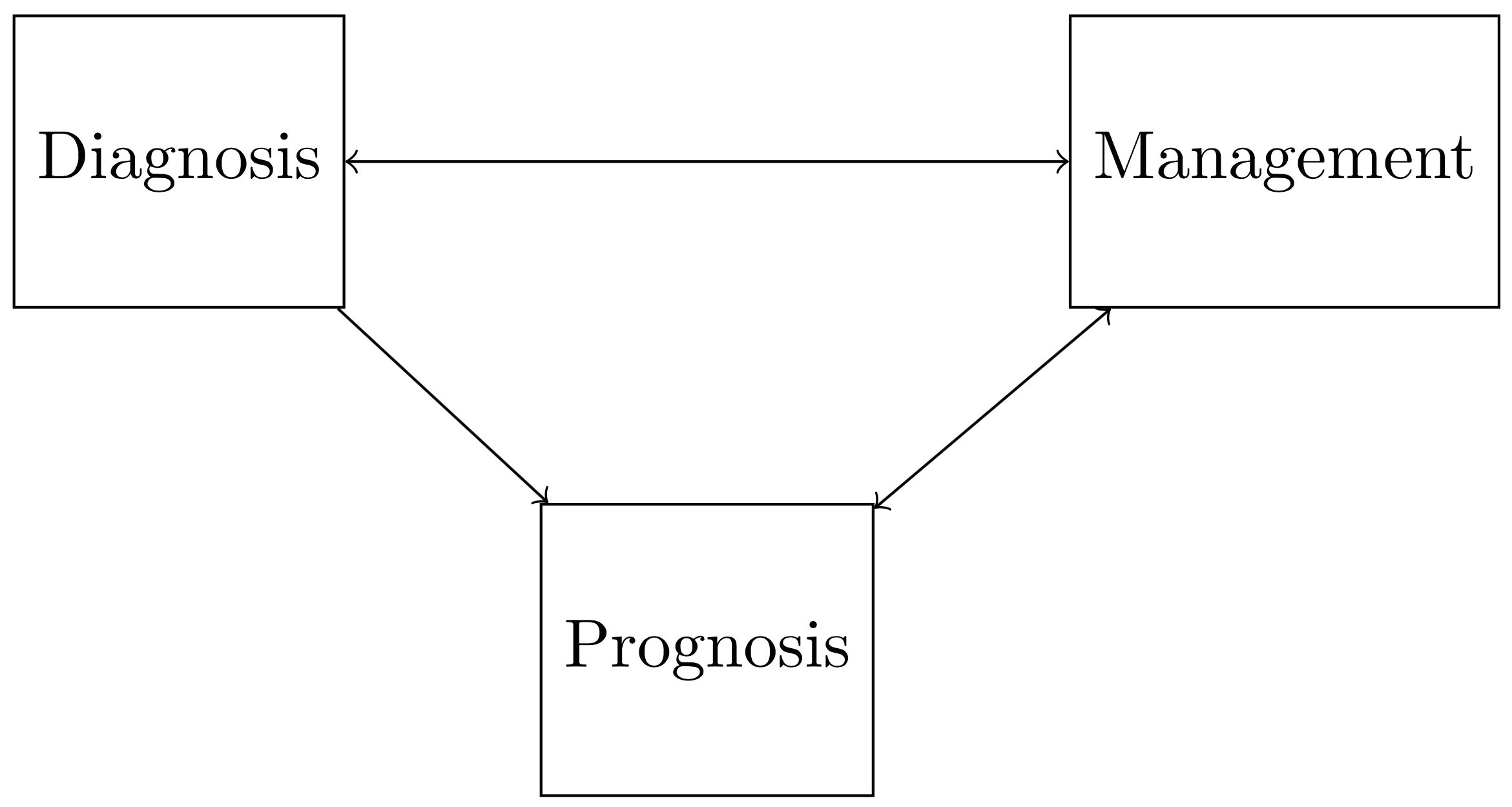

where the angled brackets $\langle f(x) \rangle$ denote the expectation of $f(x)$ under its respective probability measure. There are two clinical goals that naturally emerge from this formulation. First, one seeks to accurately estimate $\hat{\mathcal{Q} _{0}}(\mathcal{D}; \boldsymbol\Theta)$, which requires inferring the parameters $\boldsymbol\Theta = \lbrace \boldsymbol\theta _{\omega}, \boldsymbol\theta _{S} \rbrace$ and minimizing $\sigma _{\mathcal{Q}}^2$. Plainly speaking, this amounts to accurately predicting the patient’s prognosis (which is determined by the parameters that govern the quality and survival functions, $\boldsymbol\Theta$ ), as well as reducing the uncertainty in that estimate (which can be done by minimizing $\sigma _{\mathcal{Q}}^2$ ). The second goal that emerges from this formulation is to develop some plan to maximize $\hat{\mathcal{Q} _0}(\mathcal{D}; \boldsymbol\Theta)$: that is, to intervene such that the patient’s predicted quality-weighted longevity is maximized. One can appreciate that prognosis after the clinical encounter (the estimate of $\hat{\mathcal{Q} _0}(\mathcal{D}; \boldsymbol\Theta)$) depends on management (i.e. the method by which $\hat{\mathcal{Q} _0}(\mathcal{D}; \boldsymbol\Theta)$ is maximized), which depends on diagnosis. These dependencies are depicted in the figure below. It can be appreciated that estimating and optimizing $\hat{\mathcal{Q} _0}(\mathcal{D}; \boldsymbol\Theta)$ is a complex process by which a clinician must continually evaluate diagnosis, management, and prognosis jointly.

A natural approach to the above problem is one in which the clinician iteratively estimates and maximizes $\hat{\mathcal{Q}_0}(\mathcal{D}; \boldsymbol\Theta)$ over time as more information is gathered.